The goal of eradicating poverty in context of increasing vulnerabilities

Gyan Bahadur Adhikari1, Praman Adhikari, Kritika Lamsal

Rural Reconstruction Nepal (RRN)

Despite being one of the first countries in the world to prepare a preliminary national report2 on the implementation of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), Nepal is taking longer than many to come up with a comprehensive plan of actions towards reaching those goals. The National Planning Commission (NPC), the apex body that formulates periodic development plans in Nepal and which is also taking a lead in implementation of SDGs, recently issued a press release3 disclosing the formation of two high-level committees, namely the National Steering Committee chaired by the Prime Minister and Implementation and Monitoring Committee chaired by the Vice-Chairman of the NPC, along with nine thematic groups to roll out and implement the SDGs.

Though the Economic Management Division of the NPC Secretariat has been declared as the SDG Secretariat, detailed action plans for all bodies and groups must be set up immediately to demonstrate true commitment to the global goals as achieving the SDGs calls for action rather than rhetoric.

Profit vs. Service: Questionable Public Private Partnerships (PPPs)

The aforementioned committees for SDGs implementation are mandated to include representatives of civil society, confederations and other stakeholders under various names as members. This is the first time that private organizations have been brought into high-level official committees influencing implementation of the globally agreed goals. At the end of 2015, the government introduced the Public Private Partnership (PPP) policy followed by trainings and programmes emphasizing the need for private investment to finance public services, especially for the SDGs.

Even though Nepal has just begun experimenting with PPPs, with only a few projects completed and many underway, there are red flags that shouldn’t go unnoticed. The ultimate need of private entities to maximize profits in order to stay in business is fundamentally incompatible with protecting the environment and ensuring universal access to quality public services.4 This is evident in the failure of Kathmandu Upatyaka Khanepani Ltd. (KUKL), the first PPP scheme in 2008, to deliver its promise to improve the water delivery efficiency around Kathmandu Valley. 5 KUKL management is allowed to have a team of 1,207 employees but the number of staff currently hovers around 1,050, among which 70 percent are non-technical, the majority working as accountants or administrative staff.6 Lack of skilled technical staff is seen to be a result of heavy political influence, high-handed conduct and resort to nepotism. High water tariffs, undersupply of water and high deficits also shows the inefficiency of the board, chaired by the representative from a private sector, along with KUKL.

Fully 170 million litres of water are expected to flow from the Melamchi River in Sindhupalchok to Kathmandu Valley every day starting in September 2017 with KUKL as the sole distributor. As the tunnel work is coming to close, the much-awaited project that is expected to end the woes of the public suffers due to delays in crucial decisions by the institution.

Though PPPs have some advantages that might benefit a country with an underperforming public sector, the simple fact that private companies are there for profit rather than service provision shows the risk involved in PPPs for basic amenities for survival, like food, fuel or water. The solution might be to prioritize the involvement of private sector partners in profit-earning sectors as opposed to basic amenities.

Increasing privatization and the state of the public sector

In Nepal, privatization was started seriously after the restoration of democracy in 1990 as the new government privatized some enterprises in order to improve efficiency, reduce government administrative and financial expenses and increase private sector participation, as well as ensure effectiveness in service delivery.

During the period from 1992 to until recently (fiscal year 2070/71), 30 state-owned enterprises (SOEs) have been privatized using a variety of different modalities, such as assets and business sales, share sales, management contract, lease, liquidation and dissolution.7

The privatization exercise witnessed a number of constraints, including government policy inconsistencies, little awareness of the schemes, huge SOE debts, corruption and lack of transparency. It is worth noting that between 2008 and 2012, the privatization exercise was suspended and only restarted in 2013. Privatization has also suffered setbacks because of the poor government public awareness campaign, specifically to those more than 70 percent living in rural areas.

Privatization in education sector aggravates inequality

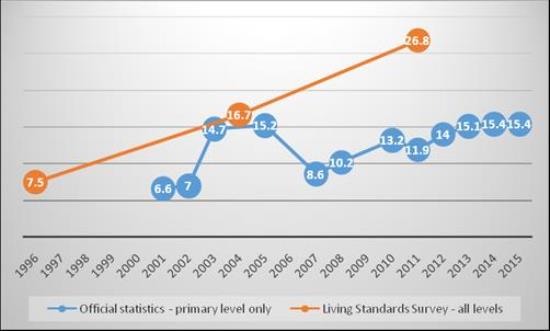

A parallel report8 submitted by the National Campaign for Education-Nepal, the Nepal National Teachers Association (NNTA), the Global Initiative for Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, and other partners, on the occasion of the report of Nepal during the 72nd session of the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child in 2016 has analysed the impact of privatization in the education sector. It states that according to 2014 official statistics, community (public) schools represented 84.1 percent of all schools, and institutional (private) schools accounted for 15.9 percent. This trend was stable in 2015 with 15.3 percent of children officially enrolled in private schools (see graph below). The number of private schools is however underestimated, due to the high number of unregistered private schools that are not accounted for in the official statistics. The 2010/2011 Living Standard Survey shows for instance that 27 percent of children attend private schools. Overall statistics also mask large disparities between urban areas, where an average of 56 percent of children, and up to 80 percent, are enrolled in private schools, and rural areas, where only 20 percent of children attend private schools.

Percentage of children attending private school (UNESCO, primary level) and the Living Standard Survey (all levels)

Source: Central Bureau of Statistics, Nepal Living Standards Survey 2010/11, Statistical Report, Vol.1, November 2011, p. 84, and http://data.uis.unesco.org/ |

The result of this privatization in the education system is a highly segregated society according to socioeconomic background as costs of private schools aren’t suited for the poor. In Nepal, children generally attend different types of schools, according to their socioeconomic background. Almost half of the pupils enrolled in private schools belong to the 20% richest quintile of the population, while 50% of the pupils enrolled in government schools belong to the two poorest quintile of the population.

Type of school attended by individuals currently in school according to their income quintile

(figure in italics and highlighted when above the average)

|

Consumption Quintile |

Community/Government |

Institutional/ Private |

Other Schools/Colleges |

|

Poorest 20% |

92.7 |

6.4 |

0.9 |

|

Second |

86.5 |

11.2 |

2.3 |

|

Third |

79.1 |

19.8 |

1.1 |

|

Fourth |

64.3 |

34.7 |

1 |

|

Richest 20% |

39.0 |

60.1 |

0.9 |

|

Average |

71.9 |

26.8 |

1.2 |

Source: Central Bureau of Statistics, Nepal Living Standards Survey 2010/11, Statistical Report, Vol.1, November 2011, p. 99.

Implementing the SDGs: Need for a Clear Roadmap

The preliminary national report on SDGs has an entire chapter that delves into the current status of the proposed SDGs and their targets as well as existing institutions for their operationalization. However, definite public bodies or specific programmes haven’t been mentioned in the vague description of Nepal’s present efforts implementing the goal. Though Nepal has prepared sensible policies, the absence of a concrete plan and political will often leave the policies without proper monitoring mechanism, or at worse unimplemented. This presents a great need for a precise, clear and concrete plan for action that will serve as a roadmap during the implementation of each of the SDGs.

Poverty eradication: a long road ahead

Nepal has made some slight progress with extreme poverty reduced from 31 percent in 2004 to 24.8 percent in 2014, narrowing the poverty gap from 7.6 percent to 5.6 percent, and nationally defined poverty at 23.8 percent.9 Looking at the current trend of economic growth, though Nepal might show significant improvements, the achievement of SDG 1 which has targeted reducing the poverty gap to 2.8 percent, and both extreme poverty and nationally defined poverty to less than 5 percent seems unlikely.

Despite apparent success in decreasing the proportion and number of poor people, rising income inequality has remained a considerable policy challenge although governments take up pro-poor redistributive policy and considerable public spending on social protection. Persistently high income inequality has been creating social polarization and mass discontent. A basic development outcome in any country is the improvement of the living standards of its citizenry. Contrary to official government statistics, in reality, the benefits have not ‘trickled down’ to the vast majority of people to a level where it has improved or enhanced their living standards in a notable manner.10

However, with more than a tenth (11.3%) of the total national budget currently spent on social protection,11 the target of increasing social protection budget to 15 percent of the national budget is highly achievable. A 2011 law established a Social Security Fund Secretariat to administer a contributory social insurance scheme covering old-age, disability, unemployment and various other insurance programmes. Public- and private-sector employees already contribute 1 percent of their earnings to the fund.12 The need for review has been pointed out on several occasions as the fund is purely based on contribution, and public and private sector employees are still contributing 1 percent of their total salaries.

Unprotected Informal Sector

The 7.9 RS magnitude earthquake on 25 April 2015 hit 36 of the 75 districts, among them 14 worst hit districts13 where 8,800 people were killed, thousands injured and an estimated 1 million residents displaced. Nepal’s development efforts faced a serious jolt when the large earthquakes and aftershocks of April and May 2015 affected almost a third of the country's population and resulted in a loss of more than NRP 700 billion of damage to human settlements, infrastructure and archaeological sites.14

In Nepal, it took nine months to set up a body to take charge of earthquake recovery, the National Reconstruction Authority (NRA), established in December 2015 and charged with the authority to coordinate the recovery effort between various government and non-government organizations, as well as Nepal’s international development partners.

After the earthquake, the plight of the people living in Kathmandu’s camps was further compounded by their low levels of education and skills. Most are low-skilled workers who earn a living as housemaids or work in the construction sector, small hotels, catering, sweet shops, carpentry, carpet factory, security and other such enterprises. There are also those who sell food on footpaths. Even a month after the earthquake, their earnings had not reached previous levels. Those in the transportation sector were not earning enough to pay for vehicle rental and repair due to a decrease in the number of passengers, while those who run their own small business or even footpath shops were not getting enough customers to earn a decent income15

India’s trade and transit embargo

India’s undeclared blockade (23 September 2015 to 23 February 2016) on all goods at the Indo-Nepal border led to severe difficulties for ordinary people to maintain their normal lives. These acts of collective punishment are deplorable and are totally against the concept of the South Asian Free Trade Area (SAFTA) 2004 and other agreements such as Indo-Nepal Treaty of Peace and Friendship 1950, the Motor Vehicle Agreement among Bangladesh, Bhutan, India and Nepal (BBIN) 2015, the Convention on Transit Trade of Land-locked States (1965) and United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.

As Nepal relies heavily on imports from India, this embargo led to massive shortages of fuel, construction materials, cooking gas and medicines, among others, hampered Nepal’s economy and left the rebuilding of the entire nation in limbo. UNICEF released a statement16 that said that more than 3 million children under the age of five were at risk of death or disease during Nepal's harsh winter months, because of a severe shortage of fuel, food, medicines and vaccines. Similarly, many national and regional civil society networks denounced the embargo as an inhumane act against humanity, which impacted Nepal’s economy exponentially more than the 2015 earthquake. Cold weather, dry landslides and destruction of roads placed additional burdens on the already affected population.

This unforeseen setback has definitely impacted the country’s ability to achieve the SDGs on time, as seen in the postponement of Nepal’s graduation from the Least Developed Countries from 2022 to 2030. To avoid further setbacks, an analysis of the effects that SDGs can face in the post-earthquake scenario along with proper mitigation measures must be incorporated into the implementation of the localized SDGs.

Youth and the Road to 2030

Nepal currently has the largest productive youth population compared to the dependent population in its history with 58.7 percent of the total population in the age group 15-59 years.17 With more than half of its population in this category, it is necessary to bring them into the forefront of development, not just as beneficiaries but also as actors. On that note, Nepal is all set to implement Youth Vision 2025, a ten-year strategic plan for the overall development of youth in the country. In this regard, UNFPA has been an active advocate with numerous undertakings, such as conducting mock youth parliaments, facilitating the participation of young people in localizing the SDGs, and partnering with youth organizations to catapult youth to the center of SDG implementation.

With over 53,000 youth leaving the country every year for job opportunities,18 it is necessary to tap into this abundant human resource for development. Creating platforms for engagement of youth, providing them with skills for self-empowerment and accommodating them in national platforms is one of the most realistic ways a fragile nation like ours can achieve development, and also the SDGs.

Conclusion and recommendations

Nepal has faced one socioeconomic shock after another in a relatively short period of time, be it the ten- year civil war or the devastating earthquake or the unstable government, which has changed 25 times since the restoration of democracy in 1990. The current political wrangling is no longer hidden, with political parties openly prioritizing their personal needs over those of their citizens, refusing to come to consensus on urgent national matters and failing to create a nurturing environment to foster economic and human development.

The new Constitution of Nepal, which came into effect in 2015, replacing the Interim Constitution of 2007 is the result of a rigorous democratic exercise of about eight years. The promulgation of the new Constitution marks the conclusion of the nationally-driven peace process initiated in 2006 and also institutionalizes significant democratic gains and aspirations of the people including the establishment of a federal and republican system.

The new federal system might just be an opportunity for establishing robust local governance in Nepal. Though there are some political hiccups in the southern part, Nepal is preparing for its local elections in full swing which if successfully completed might contribute to stability in the country. The Constitution has arrived with its set of complications and has faced grievances, but the existence of the document itself is a beacon of hope for many. The much-awaited Melamchi drinking water project is estimated to arrive Kathmandu at the end of this year. These small feats could just be a sign that Nepal is finally moving somewhere after years of stalemate. It is time to capture this on a bigger scale by capitalizing on the mass population of the younger generation to bring about a greater economic development.

With a suitable environment for business to thrive, a young generation to get engaged and public sectors to strengthen, the transitioning country has a chance to create a better system as it changes. If the newly formed committees for the SDGs are based in a sound political environment supported by a majority of its citizens, it will exponentially increase the country’s shot at achieving the SDGs. For this to happen, the following steps need to be taken:

- Clear stands should be taken against the iniquitous nature of the political economy and the concessions being given to industry, multinationals and corporate firms to continue with growth and profit- maximisation at the cost of human welfare.

- As universal social protection is key to addressing the ever-widening inequalities, vulnerabilities and discrimination, the introduction and implementation of universal social protection systems is now a development imperative and must be a stand-alone goal with targets.

- Investments in non-farm sector employment in rural areas and long-term plans for reviving sustainable agriculture, marketing by small producers and better infrastructure should be done for the creation of new jobs which will reduce the flow of labour migration.

- A policy should be introduced to guarantee a safe and secure home for poor families to realize their rights to secure housing.

- The newly formed committees for the SDGs should from a comprehensive plan that will serve as roadmap for the implementation of activities related to every goal as well as to monitor progress on a periodic basis.

- The Public Private Partnership Policy should be revised to encourage investment in purely profit- earning sectors with negligible social costs.

Notes:

2 View the full report at http://www.undp.org/content/dam/nepal/docs/reports/SDG%20final%20report-nepal.pdf?download

3 View the press release at http://www.npc.gov.np/images/category/pressrelease_pmsdg.pdf

4 D. Hall, Public Services International Research Unit, Why Public Private Partnerships Don’t Work, 2008.

5 G. Siwakoti, “Reality Check”, July 2011, pp. 31-35.

6 R.D Sharma, The Kathmandu Post, November 2016; available at: http://kathmandupost.ekantipur.com/news/2016-11-07/kukl-in-a-shambles-as-water-is-channelled-from-melamchi.html)

7 State Owned Enterprises Information 2072 : Yellow Book [Nepali version], p.23

8 Parallel report from Nepal for UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, Segregating education, discriminating against girls: privatisation and the right to education in Nepal in the context of the post-earthquake reconstruction, April 2016, pp. 7-13.

9 UNDESA, 2015, Annex IV a.

10 SAAPE, South Asia and the Future of Pro-People Development, 2016, pp. 22-23.

11 UNDESA, 2015, Annex IV a.

12 U.S. Social Security Administration, Social Security Programs Throughout the World: Asia and the Pacific, March 2013.

13 Bhaktapur, Dhading, Dolakha, Gorkha, Kathmandu, Kavrepalanchowk, Lalitpur, Makawanpur, Nuwakot, Okhaldhunga, Ramechhap, Rasuwa, Sindhuli and Sindhupalchowk.

14 National Planning Commission, Post Disaster Needs Assessment, 2015 (with subsequent assessments).

15 SAAPE, South Asia and the Future of Pro-People Development, 2016, pp. 80-81

16 See full press release at: https://www.unicef.org/media/media_86394.html

17 UNDESA, World Population Prospects, 2015, Table S.6.

18 UNFPA and YUWA-Nepal, My SDGs, My Responsibility – A youth guide for sustainable development in Nepal, 2016.